A feature of colonialism was the marginalisation of the colonised people in any political discourse. Their views didn’t really matter.

This is still a feature of world politics even if colonialism has largely been replaced by a new form of imperialism, whereby the major western powers, particularly the United States, still determine much of what goes on in the less-developed world.

Nobody asked the Afghani or Iraqi people before the United States invaded their countries in 2001 and 2003. The US then decided how the wars would be fought, with little reference to the local people. In Afghanistan civilian casualties in the war went largely unreported. The first official American reports on any raid were all about the number of insurgents killed. Only later would the US military reluctantly admit that some civilians might have been killed.

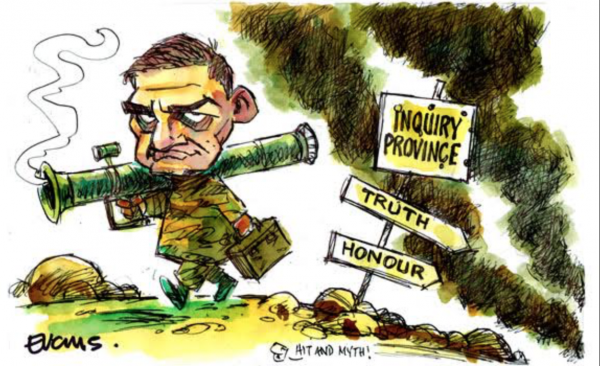

The NZ Defence Force reporting on the SAS raid on two Afghan villages in August 2010 follows the US pattern. First the NZDF said that no civilians had been killed in the raid. Now it says it is possible civilians died.

In terms of confirmed deaths the NZDF says nine (unnamed) insurgents were killed. In Hit and Run Nicky Hager and Jon Stevenson say no insurgents died but six (named) civilians were killed. Their information comes from the villagers.

I support an inquiry to sort out what really happened in Operation Burnham. But with or without it, surely a path to the truth lies in evidence provided by the affected villagers, some of whom appear to be accessible via cell-phone or email – or face-to-face in Afghanistan. The villagers are now represented by Kiwi lawyers, who are in touch with them.

Defence Chief Tim Keating and the Prime Minister exhibit the “colonial” reflex in completely ignoring the villagers as a source of information. Bill English looked at a few American videos of the battle and considered that to be enough to reject any inquiry. Keating didn’t consider evidence from the locals as relevant enough to mention.

Keating and English also didn’t think it important to respond to evidence that an SAS soldier beat one of the Afghan locals, Qari Miraj , who was then passed on to the notorious torturers in the Afghan National Directorate of Security. I can’t help thinking that the beating and the torture may have been relevant to Mr English if Qari Miraj had been a Westerner, rather than an Afghan.

While Keating and English may be displaying their “colonial” bias, others in the Defence Force were not. The Hager and Stevenson book was made possible by some SAS soldiers, upset at what they saw, coming forward with evidence of what went wrong.