Free speech is dangerous. That’s clearly the view of top security officials in Britain and New Zealand.

Firstly, to Britain. One Whitehall official, angry at the Guardian’s coverage of the Edward Snowden documents,

told Guardian editor Alan Rusberger

: “You’ve had your debate. There’s no need to write any more.” These chilling words accompanied a British government order that the Guardian destroy its computer hard drives containing the Snowden documents. The Guardian complied, but only because they had copies of the documents stored abroad.

The secret state might try to block public debate on intelligence matters, but surely the much-vaunted oversight bodies will protect our right to know? If you believe that it might pay to listen to the chair of Britain’s parliamentary Intelligence and Security Committee, Sir Malcolm Rifkind.

Interviewed by the

BBC’s Today programme

, Rifkind justified the destruction of the Guardian’s hard drives, arguing that whatever a newspaper editor might “genuinely think” there is an “inability to judge [intelligence material] if you are a newspaper editor or a journalist, as opposed to somebody involved in the intelligence work…” That is: only insiders are qualified to judge. Trust them, they know what they are doing. Let the watchers watch themselves.

Rifkind said the Heathrow airport detention of David Miranda (Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald’s partner) was a

“sensitive issue”

. But holding him would be justified if Miranda was carrying some of Snowden’s material showing that US and UK intelligence had “much more sophisticated [access to communications] than perhaps were previously understood” because, according to Rifkind, making this public would help the “terrorists”. There was not the slightest recognition from Rifkind of the public’s right to know from Snowden that its phone calls and emails were now being comprehensively intercepted.

Here in New Zealand, there is also little recognition of the right of journalists to protect their sources when it comes to intelligence matters. The government has not accepted the principle that journalists should not have their phone records checked or their movements monitored, as happened to Fairfax journalist Andrea Vance.

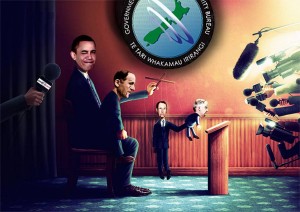

At the very time the Key government is instituting state surveillance measures which further intrude on our privacy, it puts a wall of secrecy around virtually everything to do with the GCSB, in the hope of limiting debate, particularly about the GCSB’s relations with the American National Security Agency.

Last week, for example, John Key refused to answer a

question from Green co-leader Russel Norman

as to whether the GCSB receives “funding directly or indirectly from the Government of the United States” – a relevant question given Snowden’s information that the

NSA is funding its British counterpart, the GCHQ

. Key replied, without any explanation, that it was “not in the national interest” for him to answer that question. But since when was it in our “national interest” to hide what appears to be GCSB subservience to American intelligence?

Russel Norman continued his questioning by asking the PM whether it was a “basic principle of parliamentary responsibility for the government’s finances” for Parliament to know if “the GCSB receive(s) money from a foreign government.” Key’s reply: “I am not saying it is, or is not.” Well he should. There’s an old saying that “He who pays the piper, calls the tune.”

The “we won’t answer the question on national security grounds” was used repeatedly during my time in Parliament to stymie debate on intelligence issues. It largely worked for the government because even if journalists didn’t accept the “national security” excuse, they were often reluctant to continue covering a security issue if one side in the debate, the government, wouldn’t engage. Let’s hope the media adopt a more interrogatory stance now that public sensitivity to intelligence issues has been heightened by debate over the GCSB Bill – and the media itself is becoming an intelligence target.

Among the questions worthy of the attention by investigative journalists is whether the NSA still has a desk in the GCSB’s Wellington office, as it appeared to have a few years ago, according to

evidence released by Wikileaks

.