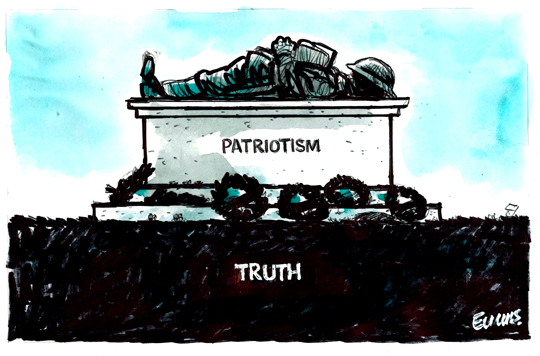

Remembering those died at Gallipoli a hundred years ago has been the right thing to do. But what’s been said at the remembrance ceremonies has often been wrong, and so dishonours the dead.

World War I was one of the two greatest tragedies ever to hit New Zealand – the other being the Land Wars and the dispossession of Maori.

We owe it to those who were killed in the World War – so many of our young men – to tell the truth about the nature of the conflict. Only by doing so can we learn from the war and avoid making similar mistakes.

Let’s correct some of the myths that have been spread over the past few weeks by those who should know better.

Firstly, those fighting in Gallipoli were not fighting for their country, New Zealand. They were fighting for a Britain and its empire, which at that time was still holding back our nation from becoming fully independent.

The Gallipoli campaign was not about defending democracy. Rather it was to help an autocratic Tsar and give Russia greater access to the Dardanelles.

The war was not about advancing freedom, but just the opposite. It was about Britain keeping its colonies, and stopping its subjects in places like India gaining their freedom. Britain ended up with more colonies, taking some from Germany. New Zealand got Samoa, which wasn’t necessarily an improvement. Arguably New Zealand was more oppressive towards Samoans than the Germans had been.

The war was not about protecting human rights. In fact, those who publicly criticised the war were sometimes jailed, and those men who refused to serve were harshly punished. Even a century later those who speak out against World War I are still being punished: On Sunday an Australian SBS reporter Scott McIntyre

was sacked

when his (truthful) antiwar comments on social media were deemed “inappropriate”.

The war had nothing to do with upholding our “values”. A central value – to give everyone a fair go – was undermined by the war. Racism reared its ugly head. New Zealanders of German origin were insulted, sacked and sometimes interned.

We weren’t fighting an “evil”, contrary to what our current Chief of Defence Force Tim Keating

has claimed

. Germany was a civilised country. Although the Kaiser had more power than the British King, Germany had a functioning parliament (the Reichstag) where MPs voiced opposition to the war

in far greater numbers than Britain

. In our Parliament the Labour stalwart Paddy Webb was almost alone in his criticism of the war. Rather than this being tolerated Webb was kicked out of Parliament and jailed for refusing to be conscripted.

The idea that Gallipoli somehow made us a nation is fanciful. New Zealanders were just as loyal to the Empire after the event as before. Go look at the war memorials if you are in doubt. We became proud of being New Zealanders well before the war partly as a result of giving women the vote and passing social legislation that was ahead of other nations, including Britain. It is no accident that the statue immediately outside of Parliament is of Liberal Prime Minister Richard Seddon (1893-1906), not some war hero.

The Gallipoli nationhood myth emerged out of a need for supporters of the war to extract something positive out of an unmitigated disaster. The idea that war is nation building has also been useful to justify New Zealand involvement in subsequent military adventures overseas, right up till today.

The nation building myth has some traction because it is psychologically hard for a people to admit when so many have died that they weren’t fighting in a good cause. But we have to accept that they didn’t make the world a better place. Yes, many of the Kiwi ANZACs fought heroically, and we can and do recognise that. But they were heroes in the wrong cause. They were victims of those who sent them to an unjust war which turned into New Zealand’s biggest 20th century tragedy.

We seem to have learnt something over the 100 years since the “Great War”.

A Colmar Brunton One News poll

on Sunday showed that 49% of New Zealanders think the main reason Kiwi troops are off to Iraq is to maintain “good relations” with America and Britain, not because it is the right thing to do. The lesson of World War I is to beware fighting in the empire’s wars. Now, of course, the empire has changed, from one under Britain, to one under America.