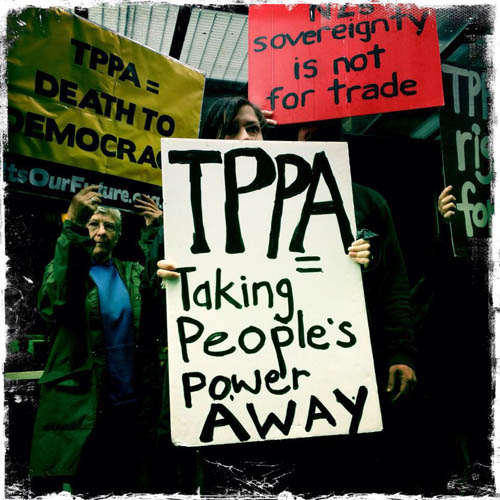

Many people have criticised the wall of secrecy around negotiations for a Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement. They fear New Zealand’s negotiators will sign a deal which undermines our sovereignty and has a big social and economic downside.

One of the main cheerleaders for the TPPA is Stephen Jacobi, the executive director of both the New Zealand International Business Forum and the NZ-US Council.

I was startled to hear him say (twice) on Radio New Zealand’s Morning Report

last Tuesday

that New Zealand’s interests will be protected because any treaty “has to be ratified by Parliament.”

That is simply not true. Under New Zealand’s present constitutional arrangement the government, and only the government, has the power to ratify treaties. Parliament has no such power.

When in Parliament I tried to change this. The main point of my

International Treaties Bill

, drawn from the ballot in 2000, was to give Parliament the power to ratify treaties. I was pleased that the then Labour government did allow my Bill to go to a Select Committee and the discussion there did produce some positive change, including more openness about which treaties and bilateral agreements our government was in the process of negotiating.

However,

in February 2003

, after the Select Committee had reported back to Parliament, Labour and National combined to vote down my Bill. Only the Greens and ACT supported the requirement in my Bill that a treaty could only be ratified by a majority vote in Parliament.

On one occasion, under pressure from its Alliance coalition partner, Labour did allow a trade treaty, the one between New Zealand Singapore, to be debated by Parliament, and a vote taken. But it was only a “symbolic” vote, easily won by Labour and National voting together. Labour had not conceded the government’s right to ratify that or any other treaty.

The only way Parliament is involved with treaties is in a consultative capacity. After a treaty is signed by the government it is tabled in Parliament and sent to Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Select Committee, to either discuss it or send it on to a more relevant select committee. From the time the treaty is tabled in the House select committees have 15 parliamentary sitting days (or 5 sitting weeks) to consider the treaty and report its views. The government says it will normally not ratify a treaty until after the five sitting weeks have elapsed, but they can if they want to. After all the select committee process is just a consultative process and the government retains the full power to ratify a treaty whenever it wants.

In any case, the five week guideline hardly gives any time for the public to properly assess a complex treaty (like the TPPA) and put together a submission to a select committee.

Of course, if a treaty the government has signed up to requires legislation to implement it, then that legislation must get a majority vote in Parliament. But many commitments the government makes in treaties don’t require legislation. For example, a New Zealand government signing up to

clauses in a TPPA agreement which undermine Pharmac

might be able to implement them by amending the regulations Pharmac operates under (which don’t come before Parliament) rather than via new legislation.

In one case where a New Zealand government did require legislation to implement at treaty it came seriously unstuck. In December 2003 the Labour-led government signed a treaty with Australia to regulate therapeutic products through a joint regime. The only problem was that Labour led a minority government and it didn’t have a parliamentary majority for the implementing legislation, in the form of the Therapeutic Products and Medicine Bill. Four years later, in July 2007, Labour had to dump that Bill. The Australian government was very angry about New Zealand not fulfilling its obligations under the Australia/New Zealand therapeutics treaty, as I found out when a parliamentary delegation I was on was ear-bashed by the then Australian Foreign Minister Kim Beazley. The joint trans-Tasman scheme is now down the drain, to be replaced by a New Zealand scheme as prescribed in the Natural Health and Supplementary Products Bill, which is awaiting committee stages in the House.

Parliament not being able to approve treaties remains a major “democratic deficit” in our constitutional system.